In the 1940s and 50s, some of the biggest names in Australian fiction were authors unknown today. People such as Gordon Clive Bleeck, Carter Brown, Don Haring and KT McCall were the leading lights of a huge local pulp fiction industry. It produced countless cheap westerns, science fiction and above all crime novels, printed cheaply with lurid covers and sold at news-stands on the street and in train stations. This piece was originally commissioned by the Wheeler Center and appeared on their website here.

In 1938, the federal government decided to levy foreign print publications. As a result of this decision, local publishing houses sprang up to fill the void, releasing hundreds of novels a month, including Westerns, racing and boxing stories, science fiction and crime. Hard-boiled and not so hard-boiled PIs became a standard feature of the pulp crime scene that flourished in Australia for two decades thereafter.

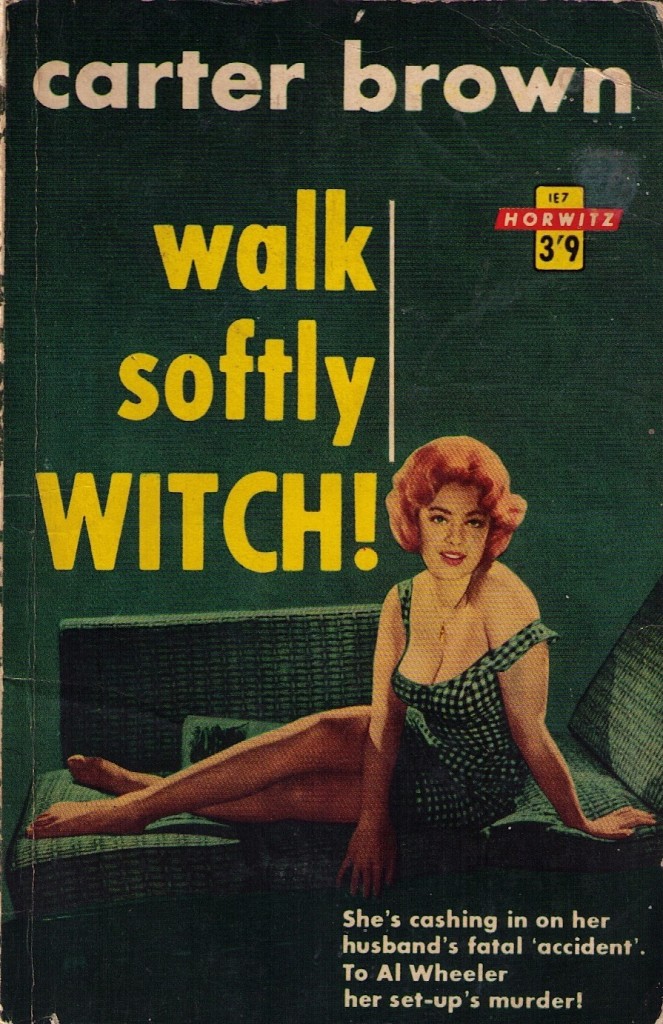

The authors are unknown today, despite some selling in the millions in Australia and abroad. Gordon Clive Bleeck wrote over 200 novels, including PI stories, while working full time for NSW Railroads. Carter Brown, the alias of UK immigrant Alan G Yates, is associated with nearly 300 titles.

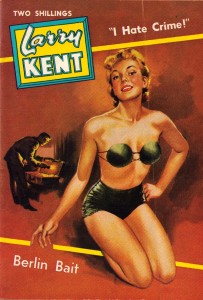

Starting off as a hugely popular radio program on the Macquarie Network, the PI Larry Kent inspired a series of novels by Don Haring, an American who lived in Australia or a time, and Queenslander Des R Dunn. Audrey Armitage and Muriel Watkins wrote over 20 novels featuring PI Johnny Buchanan under the pseudonym of KT McCall.

None of these authors would have got a gig on the ABC’s Book Show. They worked fast to meet deadlines. Books were plotted, written and released in a month, for very little financial return. Most of the plots were generic: dames, drinking, bad guys and fist fights, with a healthy dollop of cultural cringe. Many of the stories were set in America, particularly New York.

It was throwaway fiction in every sense, printed on rough paper, featuring lurid cover art that often bore no connection to the story and sold cheaply at news-stands.

Although many publishing houses continued to churn out books until the seventies, the golden era of Australian pulp fiction lasted only until 1959, when the levy ended and cheaper imports flooded in again.

Although many publishing houses continued to churn out books until the seventies, the golden era of Australian pulp fiction lasted only until 1959, when the levy ended and cheaper imports flooded in again.

It wasn’t until Cliff Hardy came along that the PI was rescued from literary obscurity. I recently re-read Peter Corris’s The Dying Trade, the 1980 debut of the now legendary fictional Australian private investigator, Cliff Hardy. A former insurance claims investigator, Hardy is a hard drinker, good with his fists, and has an eye for the ladies. As is de rigueur for jaded gumshoes, the Sydney PI’s life is always in a state of chaos.

In The Dying Trade Hardy is hired by a shifty property developer to discover who’s behind harassing phone calls to the man’s sister. It’s a violent, hard-boiled mystery, the apparent simplicity of the case inverse to the reality of what’s really occurring. No sooner has Hardy taken his first beating than the secrets of the developer’s rich and powerful family come tumbling out.

The title is fitting. Hardy’s profession is tough and dangerous. People get killed, some of them by Hardy. The Dying Trade could equally well describe the state of the private detective in contemporary Australian crime fiction.

Corris paid homage to the masters of the genre, Hammett and Chandler, as well as earlier local pulp authors, without falling into cliché or pastiche. As any author who has tried to write genre crime will tell you, that’s not as easy as it sounds.

Corris also wasn’t afraid to set his stories locally. Not only did Hardy drive a Falcon and roll his own smokes, his geographic and cultural map of Sydney is keenly informed by a very Australian, perhaps pre-economic deregulation sense of class. Hardy may bump up against pimps, thieves, con men and murderers, but in the bigger picture he knows their deeds are small-beer compared to the crimes of the rich.

Australian crime readers love police procedurals. We’re also partial to what, for want of a better term, could be called accidental PIs. There’s Shane Maloney’s political fixer cum PI, Lenny Bartulin’s second-hand book seller cum PI, Leigh Redhead’s stripper cum PI, just to name a few.

Australian crime readers love police procedurals. We’re also partial to what, for want of a better term, could be called accidental PIs. There’s Shane Maloney’s political fixer cum PI, Lenny Bartulin’s second-hand book seller cum PI, Leigh Redhead’s stripper cum PI, just to name a few.

The local scene is not totally bereft of the more traditional private detectives. There’s Kerry Greenwood’s female aristocrat Phryne Fisher, Lindy Cameron’s Kit O’Malley, my own partner Angela Savage’s Bangkok-based sleuth Jayne Keeney and, of course, Hardy, still going strong after 35 books.

To make sure I wasn’t missing anyone, I quizzed Karen Chisholm from the fantastic website, Australian Crime Fiction. She turned up one or two others, including the Gemma Lincoln series by Gabrielle Lord, but that’s it.

Why is the private investigator such a popular narrative figure? Pulp culture commentator Woody Haut has tied the fortunes of the PI as a literary and cultural icon in the US to shifts in that country’s politics.

In the thirties, when Hammett was at his peak and Chandler was getting established, official abuses of power following the Great Depression were high in the public’s consciousness. This allowed the PI to have an adversarial relationship to state power and to undertake investigations that questioned how the rich got their money, not just solve crimes for them.

The Cold War paranoia and communist witch-hunts of the fifties made public investigation something to be avoided for fear of being branded subversive. The PI as a mainstay of crime fiction declined accordingly.

Vietnam and Watergate in the seventies gave the PI genre a new lease of life through writers such as Lawrence Block and James Crumley. The economic downturn of the eighties and the growing gap between rich and poor saw further innovations to the PI character introduced by James Lee Bourke, Sara Paretsky, Sue Grafton and Walter Mosley.

In Australia, things were different. Economic protectionism, not oppositional politics, was behind the golden age of pulp crime fiction in Australia – and maybe a hint of cultural cringe. Tough libel laws, weak free speech protections and government secrecy have also meant the Australian PI never had the literary legitimacy of its American equivalent.

And delving into the affairs of the rich and powerful is no more profitable a profession in Australia than anywhere else. Maybe this explains why the majority of our fictional sleuths, like many of the writers who create them, don’t give up their day jobs.

The author acknowledges the work of Australian pulp fiction historian Toni Johnson-Woods in the preparation of this post.

Andrew, I’ve just been loaned a boxful of old Aussie pulp crime. To save me reading the lot, are there any of the old school pulp writers that you particularly recommend?

David,

Lucky guy. What is in the box? As I indicated in the post, I don’t think any of the pulp authors from the 40s and 50s were fantastic writers exactly. Carter Brown is the best known, here and internationally, but his stuff is a little bit soft boiled for my tastes. I’ve read a few Larry Kent books and quite like them. They are very much along the lines of your classic hard-boiled PIs, if that’s what works for you. Does the box have any stuff from the sixties and early seventies? There was some great pulp published during that period, which I hope to do some follow up posts on in the next few weeks. I have to admit to being particularly fascinated by a guy called Jim Kent, who did a lot of really sleazy, exploitation crime, war and sci fi books. I must do some research on him because I know next to nothing about him. Hope that helps.

Just checked through it, and it’s mostly American, some Chester Himes and others that look promising. Of the Aussies, there’s a first edition Boney, and a novel each from the sixties by Ray Slattery called ‘Surfing Highway’, Criena Rohan’s ‘The Delinquents’, William Johnson’s ‘Teenage Tramp’, and two that look interesting – Julian Spencer’s ‘The Spungers’ (“conflict explodes between a beatnik con-man and a young rebel at Kings Cross”) and Gunther Bahnemann’s ‘Hoodlum’ which I’ve started, and it’s pretty good – I think Bahnemann wrote it during a stretch at Boggo Road prison in QLD – has the flavour of Ray Mooney’s ‘The Green Light’ published by Penguin in the 80’s…

The Spoungers sounds very promising. I mean a conflict between a beatnick con man and young rebels in Kings Cross, what else could you ask for? I’m actually planning to do a post on Australian pulp fiction set in Kings Cross next up. I’ve got some amazing stuff.

Nice article. Posted link on Bish’s Beat . . .

Appreciated, Bish. thanks for stopping by.

sure it will be cool if I post it over to you for a spell, knowing it will be in safe hands, if yr keen…

Yes, post it over by all means. I would love to put it on my blog.

By the way, I should have added that Chester Himes is also great. Give him a go.

Andrew

Pingback: Peril in the sex jungle: sixties Australian pulp | Pulp Curry

Pingback: Behind the bamboo screen: Asian pulp covers of the sixties and seventies | Pulp Curry

There was some great pulp published during that period, which I hope to do some follow up posts on in the next few weeks.