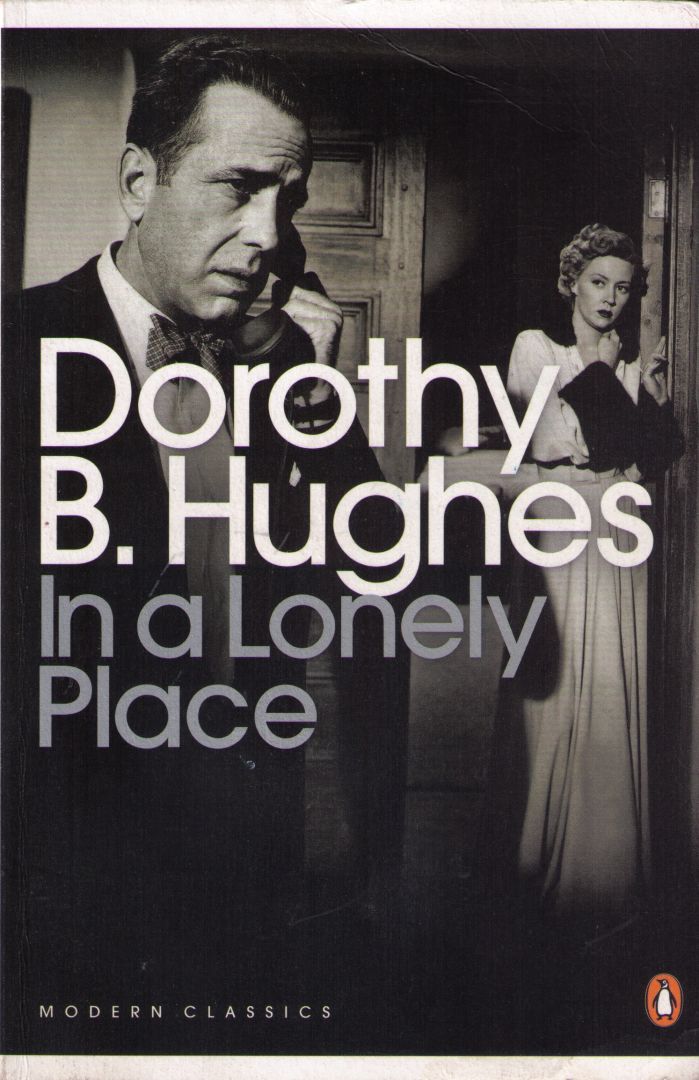

One of my favourite classic film noirs, without doubt, is Nicholas Ray’s 1950 masterpiece In A Lonely Place.

One of my favourite classic film noirs, without doubt, is Nicholas Ray’s 1950 masterpiece In A Lonely Place.

It’s a taunt, claustrophobic film that works on a very emotional level for me, much more so than most classic noirs I can think of, a devastating story about the artistic process of writing and one of the few period noirs that casts a critical eye on male violence. No matter how many times I’ve seen it, I always end up with a knot in my stomach from on-screen tension.

Dix Steele (Humphrey Bogart) is a cynical screenwriter on the verge of being washed up. He also has a very violent streak to his personality that’s obviously got him into trouble many times. His agent gives him a chance for a comeback, a gig adapting a novel into a screenplay for a director well known for his popular mainstream fare. Exactly the type of film Dix hates.

His self-sabotaging distain for the job is evident when he discovers the hatcheck girl at the nightclub he’s spent the evening in has read the book he’s been asked to adapt. He invites her back to his apartment for her take about the tome. His worst suspicions about the job confirmed, he sends the girls on her way with taxi fare and goes to bed.

He is woken early next morning by Detective Sergeant Brub Nicolai, a former air force buddy during the war, who asks him to come down to the station for questioning. Some time after she left Dix’s apartment, the hatcheck girl was strangled and her body dumped in a canyon. Dix is the prime suspect, particularly given his history of assault, drunk and disorderly and domestic violence chargers, and the lack of emotion he displays over the woman’s fate.

Luckily for him, the neighbour in the apartment opposite his, Laurel Gray (Gloria Grahame), is also called in for questioning and confirms he was at home all night. The two start a relationship and fall in love. Dix is finally happy, he can write again and starts work on the script job.

But nothing can calm his inner demons. Laurel starts to experience flashes of Dix’s violent temper, which culminates in a scene where he almost beats to death a motorist after they are involved in a near collision. She gets scared, starts to question the relationship and whether Dix really is innocent of murder. It’s an agonising slow process. Meanwhile, the cops are circling, still convinced Dix is their man for the killing.

In a gripping ending, Dix is exonerated of murder, but Laurel leaves him all the same, as she cannot stand to be around the atmosphere of violence that surrounds him. He is not the killer, but she’s seen enough of his dark side to know in other circumstances he could be. It is one of the most ‘noir’ endings to a film I can think of.

The loneliness referred to in the title works on many levels. Not only is there the sense of complete isolation Dix feels when Laurel leaves him. There’s the loneliness of the vast expanse of post war Los Angeles suburbia, as well as the difficulty and the creative compromises of being a working writer.

Bogart is great as Dixon Steele, old, cynical, world-weary. It’s probably his best dramatic performance. Grahame is luminous and totally owns the movie, the last time that could be said of one of her roles, but she’s also fragile, tentative and fearful. She and the director Nicholas Ray were going through a private separation at the time and the underlying tension from that is very evident on the screen.

I recently read the book the film is based on, written by Dorothy B Hughes in 1947. It’s interesting to compare the two. In the book, Dix is a good-looking, amoral, manipulative, hustling lounge lizard who has bummed money from a rich relative with the excuse of coming out to LA from New York and writing a crime novel.

A chance encounter reconnects him with an old air force buddy, Brub and his intelligent wife, Sylvia. Brub’s a cop now and working on the case of a mysterious strangler who has killed a number of women.

Dix starts hanging out with the couple, and when he isn’t fantasising about seducing Sylvia, pumps Brub for information about the case with the excuse he needs material for his book. But does he have far darker motives for being so interested in the stranger’s work?

At the same time, Dix meets and falls head over heels for an ambitious young actress. He knows in himself that she is out of his league and price range, but can’t help getting involved more deeply with her.

There’s a distinct whiff of Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mister Ripley is Hughes’ book, combined with a wonderfully bleak sense of what an alienating place post-war LA was and what a come down the end of the war must have been for so many men after the adrenaline fuelled high and easy camaraderie of combat.

War is hell, but peace can be a much more lonely place.

Wonderful review of a brilliant film.

Haven’t seen this one Andrew, thanks for the review…

Aye yes, a good one. I like Bogart in this role. “Old, cynical, world-weary” is a spot-on descriptin of Dix. And, from my perspective, it’s beautifully shot to.

I don’t have this one in my library, but I want to see it again. Here’s hoping it’s on Turner Classic Movies soon. ~ Mark

Saw the film a year or so ago at a Nicholas Ray retrospective at Melbourne Cinematheque. It still lives on. Very LA. And yes, Bogart’s best performance – or at least his most watchable along with To Have and Have Not. Didn’t realise there was a novel behind it all

Pingback: In A Lonely Place : The Cultural Gutter

Excellent review of one of my all time favourite films. I loved the symbolism of of Dixon’s apartment complex – the interconnecting COURTyard and staircase. A claustrophobic reflection of internalised noir?

One of my favourite lines is when Dix is questioned by Sargent Nicolai when Mildred is found strangled. Dix: You plan to arrest me for lack of emotion?

Perhaps Dixon’s embittered state of mind is a metaphor for a marginalised life. Great film.

Ray directed many favorites of mine but I can’t abide viewing his work anymore. I understand one is supposed to divorce the artist from his work(“a Grecian urn is worth any number of little old ladies”) but Ray treated his family like crap, and had a yen for

young women. Very young women. High Schoolers. That’s why Grahame seduced Ray’s son from a prior marriage, after

Ray paraded a score of teenagers in her face and bragged about it.

I am not a prude by any means, but if Ray pulled his antics today he would be in jail and getting his ass kicked every day.

Just my view, you are certainly entitled to appreciate a great movie.